Every year, I try to participate in the 10 Books, 10 Decades challenge originated by Reggie Bailey (@reggiereads on Instagram). The goal is to read, well, ten books published in ten different decades. I like the challenge because it give me a good reason to read more widely across time, tackle some of my TBR stack (not so much this year), and not just focus on new releases or releases hyped on bookstagram. Despite being entirely overwhelmed by work, I managed to finish the challenge early this year! I read half of the books as ebooks, which helped reading on-the-go, during lunch breaks or late at night.

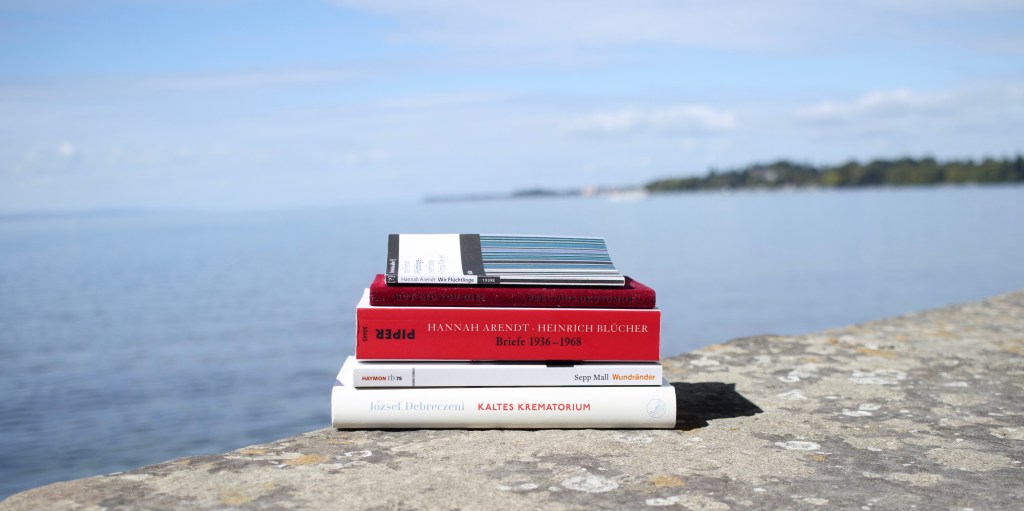

Halfway through the challenge, I decided to focus on books from the queer canon (The Beautiful Room Is Empty, Another Country, Not Without Laughter, A Few Figs From Thistles). Even though I did not consciously plan to do so, many books on this list give insight to the impact of history and totalitarianism, authoritarianism (Kaltes Krematorium, Briefe 1936-1968, On Tyranny, Wir Flüchtlinge) or unrest (Wundränder).

Precious Okoyomon: But Did You Die? (2023) ⭐⭐⭐

the boredom falls equally on all things

The stagnant unbroken brightness

oh i see a hummingbirdSun Song

Earlier this year, I saw a Artist’s Talk with Precious Okoyomon at Kunsthaus Bregenz at the opening of their exhibition ONE EITHER LOVES ONESELF OR KNOWS ONESELF. To be honest, I found the conversation with them more fascinating than either the exhibition or this book, their second poetry collection published by Serpentine and Wonder Press. Still, But Did You Die? is a nice contribution to contemporary poetry.

Timothy Snyder: On Tyranny (2017) ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Life is political, not because the world cares about how you feel, but because the world reacts to what you do.

I read Snyder’s slim volume on the lessons from the 20th century in advance of Trump’s reinauguration – and wrote about it at the time. The book becomes more important every day, globally.

Sepp Mall: Wundränder (2004) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Was meinst du, wie oft ich mir das habe anhören müssen, all dieses Gerede. Dieses Geschwätz von der richtigen Sache, all diese Luftschlösser, Verbohrtheit.1

I read Wundränder by Sepp Mall during our vacation in Meran. Set in 1960s South Tyrol, the novel intertwines the lives of two young protagonists – Paul and Johanna – whose families are quietly entangled in the region’s political unrest and bombings.

A sparse, compressed, poetic novel – not about the struggle for freedom or grand occupier politics, but about what lies in between, what follows, and what lingers at the edges. It dwells in the in-between spaces, revealing that in such close quarters, there can be no clear fronts – only many left behind.

Hannah Arendt, Heinrich Blücher: Briefe 1936-1968 (1996) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Bleib mir gut wie ich dir. Es sind lausige Zeiten.2

– Heinrich Blűcher to Hannah Arendt, 12.4.1952

This collection of letters between Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher offers an intimate glimpse into one of the twentieth century’s most profound (intellectual) partnerships, revealing the emotional depth and philosophical exchange between the political theorist and her husband. These letters, spanning over three decades, unveil a tender, vulnerable Arendt and trace the evolving bond between two extraordinary thinkers navigating love, thought, and history together.

What’s most endearing about the novel is that most letters read not as philosophical treatises, historical documents, or romantic letters, but regular notes between married people: A bit of flirtation, intimate-but-mundane details of everyday life, gossip about co-workers, rants about university admin, etc.

Edmund White: The Beautiful Room is Empty (1984) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Then I caught myself foolishly imagining that gays might someday constitute a community rather than a diagnosis.

Edmund White’s The Beautiful Room Is Empty is a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novel that traces a young gay man’s journey through repression, desire, and self-discovery in mid-century America. Celebrated for its candid portrayal of gay identity, the novel earned White the first Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction. I put this novel on my reading list after White passed away earlier this summer.

In many respects, The Beautiful Room is Empty is in conversation with the Joan Nestle and Leslie Feinberg work I read last year, if only for the fact that the working-class femme or butch lesbian perspectives do not appear in this book. I enjoyed this novel, and am planning to read the two other parts of the trilogy.

James Baldwin: Another Country (1962) ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Strangers’ faces hold no secrets because the imagination does not invest them with any. But the face of a lover is an unknown precisely because it is invested with so much of oneself. It is a mystery, containing, like all mysteries, the possibility of torment.

James Baldwin’s Another Country is a fantastic novel. A daring, emotionally charged exploration of race, sexuality, and identity set in 1950s New York City. Through the tangled lives of writers, lovers, and outsiders, Baldwin exposes the raw ache of (queer) longing and the fractures beneath America’s social veneer. As Colm Toíbín writes in his introduction, in Another Country “masculinity is a nightmare from which his characters cannot awake.”

József Debreczini: Kaltes Krematorium (1950) ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

In der Dunkelheit suche ich nach Licht, baue hinter den geschlossenen Lidern die verlorene Wirklichkeit wieder auf.

Ich brenne im kalten Krematorium.3

Kaltes Krematorium is a harrowing memoir, written by József Debreczeni shortly after his liberation from Auschwitz and the forced labor camp Dörnhau. First published in Hungarian in 1950, the book was rediscovered over 70 years later and only recently translated into German by Timea Tankó.

Kaltes Krematorium is “mercilessly precise” as Caroline Emcke puts it in her epilogue. He details the system Auschwitz, in which the Germans are the inhumane evil that presides over everything but remains in the shadows, and the daily horror and brutality is committed by the ‘camp aristocracy’: Other prisoners, the block elders and their hierarchy.I can only agree with Caroline Emcke: Kaltes Krematorium and the experience of Auschwitz remain unique. Anyone who wants to find their bearings in the present must understand and comprehend this.

Hannah Arendt: Wir Flüchtlinge (1943) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Offensichtlich will niemand wissen, dass die Zeitgeschichte eine neue Gattung von Menschen geschaffen hat – Menschen, die von ihren Feinden ins Konzentrationslager und von ihren Freunden ins Internierungslager gesteckt werden.4

Langston Hughes: Not Without Laughter (1930) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Being colored is like being born in the basement of life, with the door to the light locked and barred—and the white folks live upstairs.

Not Without Laughter is Langston Hughes’ first novel. A semi-autobiographical Bildungsroman, the book follows Sandy Rogers, an ambiguously queer Black boy growing up in Kansas in 1912. While I’m not as fascinated by Hughes’ prose as I am by his poetry, the book gives a great insight into life in the rural Midwest for Black people at the beginning of the 20th century. I was inspired to read this novel based on this list of 9 Historical Novels by 20th-Century Queer Writers by B. Pladek for Electric Literature.

Edna St. Vincent Millay: A Few Figs From Thistles (1920) ⭐⭐⭐

Grown-up

Was it for this I uttered prayers,

And sobbed and cursed and kicked the stairs,

That now, domestic as a plate, I should retire at half-past eight?

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s A Few Figs from Thistles is a bold, witty collection of poems that explores love and female sexuality, among other themes. In the poems, including the oft-quoted “First Fig,” Millay celebrates and satirizes herself. While I could appreciate her lyricism, wit, and irreverent charm, I couldn’t quite connect with this one.

- “How often do you think I’ve had to listen to all this talk? All this chatter about the right thing to do, all these pipe dreams, all this stubbornness. ↩︎

- “Stay as good to me as I am to you. These are lousy times.” ↩︎

- “In the darkness, I search for light, rebuilding lost reality behind my closed eyelids.

I burn in the cold crematorium.” ↩︎ - “Apparently, no one wants to know that contemporary history has created a new breed of people—people who are put in concentration camps by their enemies and in internment camps by their friends.” ↩︎

Thoughts?